written component

From reading list

- Bratton, B. (2013). What’s the Point of TED? TEDxSanDiego. Available at: https://youtu.be/Yo5cKRmJaf0

In this TEDx talk, Bratton criticises how TED reduces complex ideas into simple and inspiring content. He shows that some systems are built to avoid real thinking. This was important for my project, because I am questioning the idea of “definition” itself—not just how we define, but why we feel the need to define at all. Bratton’s talk helped me think about what it means to question something. It can be deep, layered, and creative. Différictionary is based on this kind of questioning. I keep the format of a dictionary, but inside it, meaning slides and breaks. His talk encouraged me to question in more open and structural ways.

- Rock, M. (2009). Fuck Content. 2×4. Available at: https://2×4.org/ideas/2009/fuck-content/

In this essay, Michael Rock argues that form is not a passive container for content, but an active part of how meaning is made. He challenges the idea that design’s job is to “deliver” content clearly. This was important for my project, because Différictionary uses the structure of a dictionary not to organize fixed meaning, but to let meaning slip. Rock’s writing helped me understand that form itself can be critical. I use a rigid layout—etymology, definitions, quotations—but what it holds is unstable. This tension between expected form and uncertain content is central to my project, and this essay helped me see that design can question meaning through its structure.

- Kinross, R. (2004). Modern typography: an essay in critical history. 2nd ed. London: Hyphen Press, pp.158–177.

In this chapter, Kinross explains how typography is shaped by the historical and cultural context in which it appears. He shows that even design theory changes over time, depending on how and when it is used. This helped me reflect on the idea that “definition” is also not fixed. In Différictionary, I use the familiar structure of a dictionary, but not to deliver stable meaning. Instead, I try to show how the form itself carries history, and how its meaning can shift in a different context. Kinross reminded me that both form and theory are shaped by the time they exist in. This made me realise that a dictionary is not a neutral system—it already reflects the values and structures of its era.

- Rock, M. (1996). Designer as Author. [online] 2×4. Available at: https://2×4.org/ideas/1996/designer-as-author/. [Accessed 22 May 2025].

In Designer as Author, Michael Rock questions the division between form and content by proposing that designers are not just interpreters but producers of meaning. He writes that authorship is not about inserting one’s voice, but about controlling the conditions in which content is received. This gave me a new way to think about my role in Différictionary. I’m not adding meaning to definitions—I’m shaping how meaning appears, shifts, or fails. The structure of the dictionary, the gaps between entries, the rhythm of quotation and pause—all of it becomes authored space. Rock’s idea that authorship lies in construction, not creation, helped me see how I could turn the rigid form of a dictionary into a field of movement. I don’t “write” the meanings—I build the system that lets them slide. This article helped me accept that form is not neutral, and that choosing a format is already a kind of authorship.

From my research

- Johnson, S. (1755). A Dictionary of the English Language. London: W. Strahan.

This dictionary helped me understand that even the most “authoritative” systems of language are full of personal choices. Johnson includes subjective opinions and literary references in his definitions, revealing that definitions are never neutral or fixed. This supports my questioning of meaning and classification in my project. His work became a historical proof that definition-making is already a form of interpretation. It also helped me visualise Derrida’s theory of différance—that meaning is always shifting and delayed. Johnson’s attempt to order language actually reveals its instability, which inspires the way I design and reframe typographic systems.

- Derrida, J. and Mehlman, J. (1972). Freud and the Scene of Writing. Yale French Studies, (48), pp.74–117

This text forms the theoretical foundation of Différictionary. Derrida’s reading of Freud’s Mystic Writing-Pad helped me understand writing as a process where meaning is always delayed and reshaped. The concept of différance—meaning produced through difference and deferral—inspired the title of my project. “Différictionary” is a made-up word that blends différance with dictionary, to reflect how definitions in this book are unstable, in motion, and interrupted. Each entry exists not as a closed unit, but as part of a delayed chain, marked by gap pages between terms. This reading also led me to challenge the authority of definition itself. I try not to hold meaning, but to let language drift.

- Yale News (2024) A Fresh Impression: Freud’s ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’ Inspires New Reflection on Memory. Available at: https://news.yale.edu/2024/02/09/fresh-impression-freuds-mystic-writing-pad

This article introduces Freud’s Mystic Writing-Pad as a model of layered memory, where new marks do not erase the old ones but rest on top. In my project Différictionary, this idea is translated into the gap pages between each word entry. These pages do not explain the terms, but show the delay, drift, and leftover traces between them. This way of structuring reflects Derrida’s theory of différance. The reference also supports my use of film/TV quotations, which work like surface marks over deeper cultural memory. It helps place my project in a contemporary context, where meaning is often unstable, indirect, and shaped by media repetition.

- Marinetti, F.T. (1973). Futurist Manifestos. London: Thames and Hudson.

In this book, Marinetti rethinks typography as a space for energy, interruption, and surprise. He treats layout as a way to make language unstable. This helped me design the space between word entries in Différictionary. I don’t use futurist style, but I was influenced by his way of using form to reveal how meaning can shift or remain unsettled. In my book, these are not blank pages. They are visual and typographic spaces where readers can feel language sliding, breaking, or delaying. Marinetti showed me that design doesn’t just support meaning—it can question it.

- Bertolotti-Bailey, S. (2016). So-called Ephemera. [online] Available at: https://stuart-bertolotti-bailey.org/projects/writing/so-called-ephemera [Accessed 22 May 2025].

The concept of “Semantic Translation” described in So-called Ephemera influenced how I think about definition in Différictionary. It shows that language is not a way to recover truth, but a way to expose belief. I found the idea “scratch the form to reveal the content” especially helpful—it describes exactly what I try to do. In my work, I don’t aim to define anything clearly. Instead, I use the dictionary format to make meaning feel unstable, even artificial. Like the Themersons, I want to make language strange again, to show both its technical structure and its limits. Their approach also reminded me that design forms (like symmetry or layout) are not neutral. They always carry values, ideologies, or assumptions. My project uses this tension to ask: what happens when a structure built for clarity starts to slide?

- Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. (2019). Beyond Words: Experimental Poetry and the Avant-Garde. New Haven: Yale University Library.

This exhibition catalogue made me think again about how language works visually. Beyond Words shows many examples of visual and experimental poetry. The artists use layout, composition, and image to change how we read language. This gave me ideas for how I design Différictionary. I try to make definitions feel unstable by using sliding layouts, rhythm between entries, and the space between them. I was inspired by the idea that language is not only something we read—it is also something we see. It helped me realise that even a dictionary, which usually follows strict rules, can be reactivated. In my project, I want the visual form to be part of how meaning is made.

- Kaplan, A., 1946. Definition and specification of meaning. The Journal of Philosophy, 43(11), pp.281–288. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2019221 [Accessed 23 May 2025].

This article explores how meaning is defined and understood in different contexts. It argues that meanings in language are not fixed, but change depending on culture, usage, and situation. This helped shape the thinking behind my project Différictionary. I do not try to give stable or correct definitions. Instead, I design a structure where each word’s meaning can shift based on its context or reading direction. The dictionary format, which usually stands for authority, becomes a space of movement. What I found most useful in this article is the idea that meaning is always a process, not a final answer. In my project, I try to show that design does not need to explain meaning—it can create a space where meaning stays open, uncertain, and even breaks down. This reading helped me see language not as a clear system, but as something always in motion.

- Villoro, F.P. (2022). A Self-Avoiding River. BoTSL#17. Available at: https://garadinervi-repertori.blog/post/777813323868733440 [Accessed 23 May 2025].

This essay presents the river as a process rather than a fixed entity, challenging how systems are mapped, measured, and controlled. It helped me think of definition not as a stable unit, but as something that shifts across time, space, and context. The river’s geometry, constantly redrawn by erosion and human intervention, becomes a metaphor for how language behaves in my project Différictionary. I was especially influenced by the idea that “each act of measurement allows for recalibration by the authority performed over it.” Like a river, definitions are shaped by institutional, spatial, and material forces. This text gave me language to think of instability not as failure but as structure—something to design around, not eliminate.

Extended critical analyses of two of the references

- Derrida, J. (1967). L’écriture et la différence. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Derrida’s L’écriture et la différence wasn’t the first book I read for this project, but it quickly became the most important. At first, I approached the idea of “definition” as something to deconstruct or parody. But reading Derrida shifted my perspective—not simply from “what does a word mean” to “why do we assume words should mean anything stable at all?”

Written in 1967—a moment charged with political unrest and philosophical upheaval—L’écriture et la différence introduces the concept of différance, a term that merges “difference” with “deferral.” Derrida describes it as “the strange movement, the impure unity of deferring (detour, delay, spacing…)” (1967, p. 13). What struck me was not just the fluidity of meaning, but the idea that this fluidity is the very condition for meaning to exist. Meaning, in his view, is always sliding, always arriving late.

That insight fundamentally altered how I structured Différictionary. Rather than treat each entry as an isolated definition, I began to see the space between words as just as important. I inserted “gap pages”—blank or ambiguous entries that resist explanation, filled instead with drift, residue, and motion. These echo Derrida’s notion that “traces only produce the space of their inscription by giving themselves over to erasure” (1967, p. 29). In other words, meaning emerges in the wake of what’s been lost, not simply in what is present.

At the same time, I was thinking about early modernist and futurist language experiments—movements that sought to dismantle old linguistic systems to make way for the new. But Derrida taught me something different: it’s not about clearing the ground for fresh structures, but revealing how every structure already undermines itself from within.

So I began to wonder how différance operates now. Derrida used it to challenge structural certainty in the 1960s—but what does it mean when structures today no longer even pretend to be stable? In our media-saturated world, language floats across platforms, refracted and repeated until original meanings dissolve. A quote from a 2010 film sounds different in 2025—not because the words have changed, but because the cultural and emotional weight around them has shifted. They become what Derrida might call traces: residual echoes, shaped more by their context than their content.

As Derrida writes, différance “exceeds the logic of classical reason” (1967, p. 13). I’m not aiming to fix meanings in place—I’m trying to design a space where they are allowed, even encouraged, to slip.

- Micah Lexier’s Things Exist

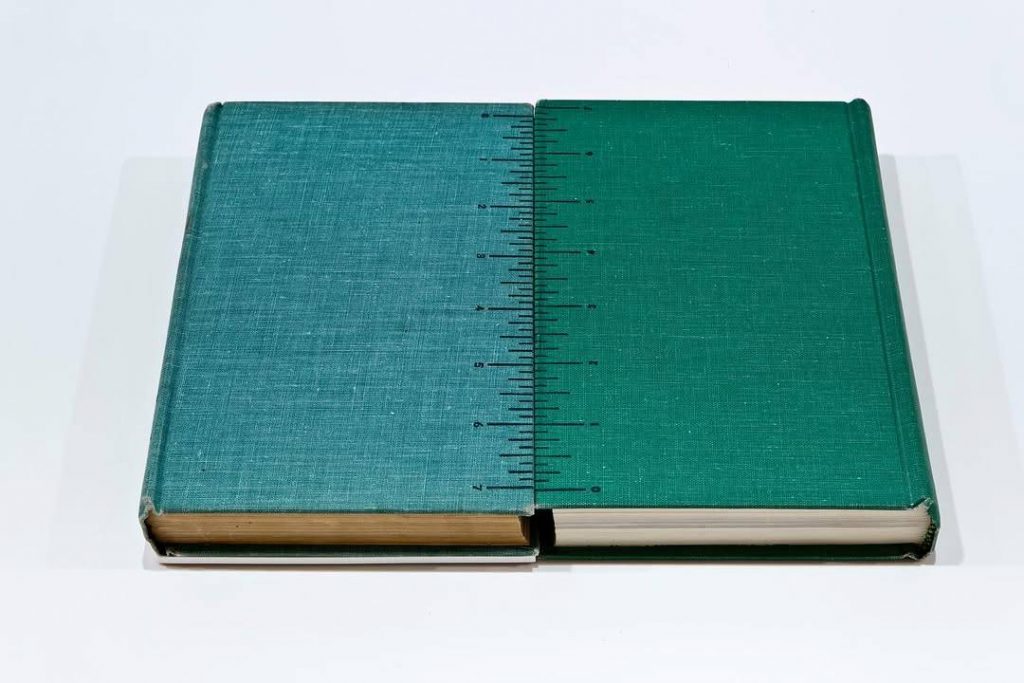

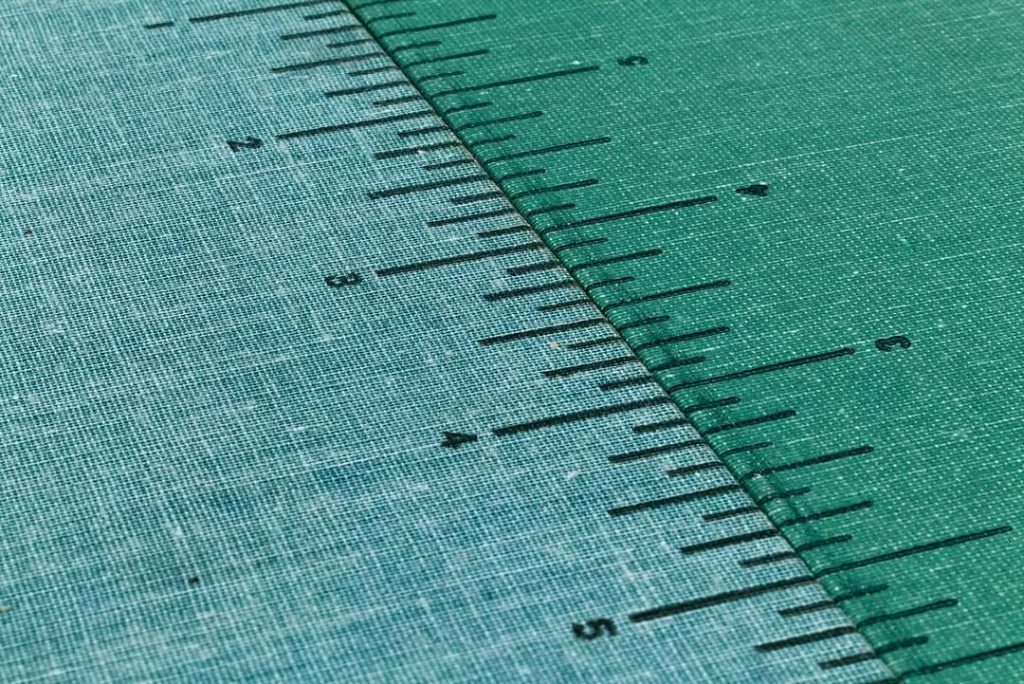

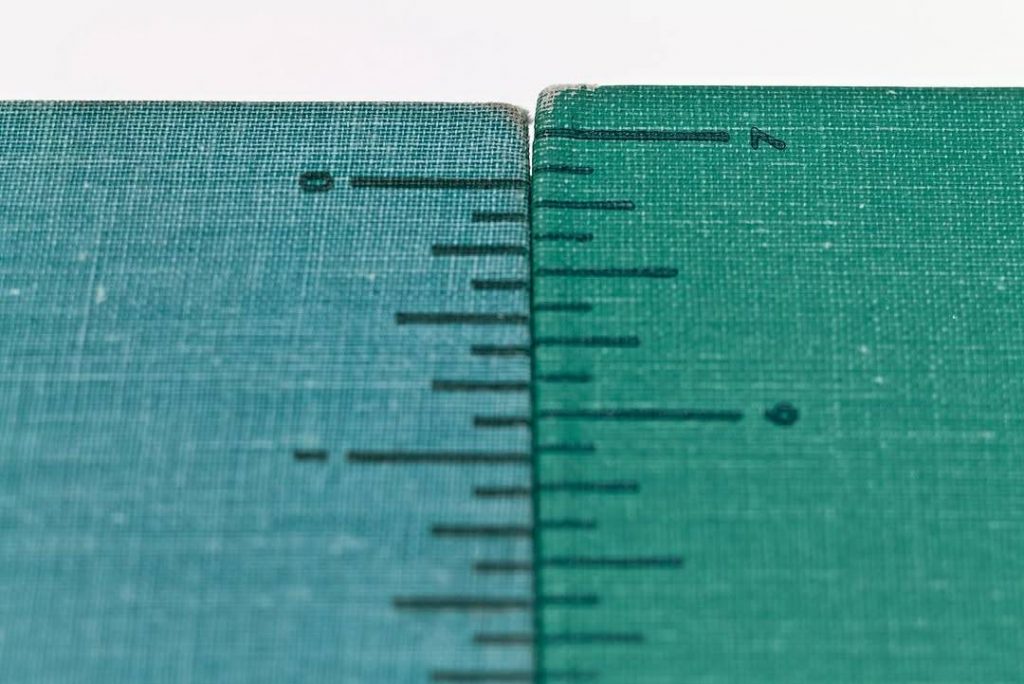

In Micah Lexier’s installation Things Exist, the framed pair of birding books made me rethink the idea of “standard.” These books are classic hardcovers—a format often linked to knowledge, structure, and authority. But Lexier shows that the rulers printed on the back covers are slightly inaccurate, because the fabric stretched during binding caused small but visible differences.

This work doesn’t make a loud statement through text or language. Instead, it uses the material’s own imperfections to quietly question the idea of precision. It doesn’t destroy the standard—it just reveals its instability by showing small differences. This made me realise that a standard doesn’t need to be challenged through theory. Sometimes, it just needs to be shown differently.

In my project Différictionary, I also use a highly structured format: the dictionary. But I’m not trying to build a new system of definitions. I use gap spaces, shifting layout, and floating quotes to show that definitions themselves are not fixed. Like Lexier’s rulers, which look accurate but aren’t, I want my design to show that definitions only appear stable because they are bound that way.

Lexier’s piece is also a quiet reference to Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages, where even something “precise” can be changed through small gestures. This method of questioning systems through form—without being loud—has influenced me a lot. Instead of attacking authority directly, I try to let the format speak for itself, and let the most “reliable” structures slowly loosen from within.